The 1986 EDSA People Power Revolution is known as a symbol of Filipino resilience and unity in times of oppression. The four-day demonstration was the result of the people’s anger and discontent in the totalitarian rule that would willingly use brute force to get its way and had slowly diminished the nation’s economy in its greed. So, what happened during this revolution and why do we continue to commemorate it today, 37 years later?

Martial Law and snap elections

Through Presidential Proclamation 1081 in September 1972, then Philippine President Ferdinand E. Marcos Sr. placed the nation under Martial Law, which gave military authorities the power to make and enforce laws. According to Marcos, this was in response to the threat of Communist insurgency and unrest in the Philippines. For nine years under this law, there were numerous cases of human rights abuse and arrests of the media and the opposition.

Marcos formally lifted Martial Law in 1981, but his rule did not end there. In his effort to prove popularity and solidify the support of the U.S., Marcos announced that he will be holding snap elections on February 7, 1986. His strongest opponent was Corazon “Cory” Aquino, widow of the late Senator Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr. who was assassinated on August 21, 1983. Ninoy Aquino was a known critic of Marcos and his administration.

Results of the snap elections were released and Marcos proclaimed himself as the victor on February 20, 1985. However, many had called out the elections’ validity and fairness due to the administration’s influence. A team of multinational observers reported cases of vote-buying, ballot tampering, and disenfranchisement.

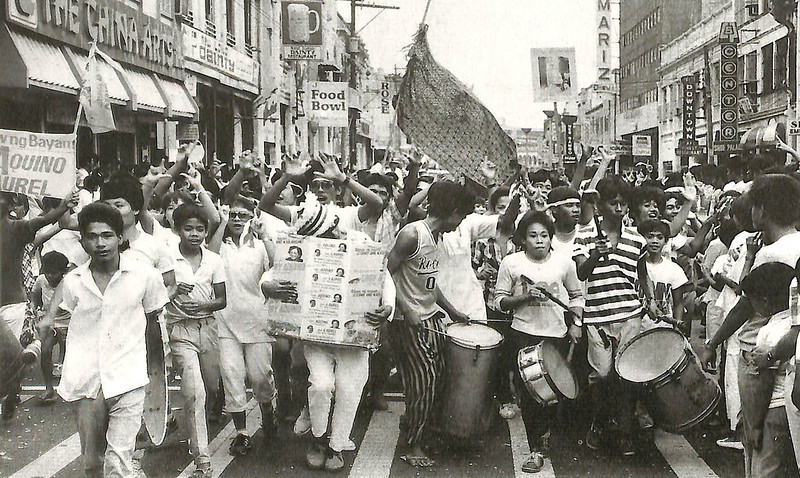

On that same day, Cory Aquino led a people’s victory rally at Luneta and called for civil disobedience against the Marcos Administration.

The 1986 EDSA People Power Revolution

February 22 – Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile was preparing his speech for the following day when he intended to proclaim himself as head of a ruling junta. Enrile and the Reform the Armed Forces Movement (RAM) had been plotting a coup with Colonel Gregorio “Gringo” Honasan leading a group of rebels to attack the Malacañang Palace and arrest President Marcos and his First Lady, Imelda. However, information of this had been leaked to Armed Forces of the Philippines Chief of Staff Fabian Crisologo Ver, which gave him ample time to double the Palace’s security. At this time, President Marcos was meeting with United States Ambassador Stephen Bosworth and Philip Habib, U.S. President Ronald Reagan’s personal envoy to Marcos, to discuss the recent elections and the political situation of the Philippines. The two had advised Marcos to remove Ver of his post.

Ultimately, Enrile and Lieutenant General Fidel V. Ramos headed to Camp Aguinaldo and announced their defection from the Marcos administration. While Enrile and Ramos were fortifying their defenses in the camp, Manila Archbishop Jaime Cardinal Sin had gone on Radyo Veritas to call on people to support the two. “Leave your homes now. I ask you to support Mr. Enrile and Gen. Ramos, give them food if you like, they are our friends,” the archbishop said.

Meanwhile, Aquino was in Cebu to thank her supporters and promote her program of nonviolent protest. She also asked for the people to boycott Marcos crony-owned businesses. Aquino was then secured in the Carmelite convent for her protection.

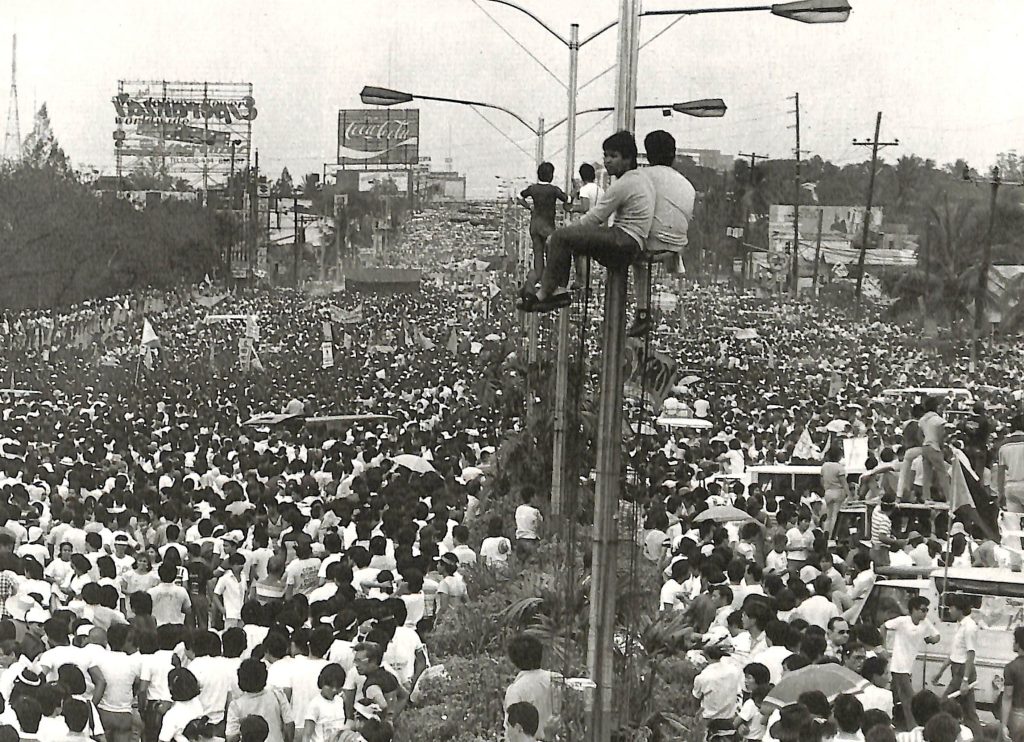

News of the Enrile-Ramos defection and the call of the archbishop had drawn crowds of people to Camp Aguinaldo and Camp Crame, which were both located along Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (EDSA) in Quezon City.

February 23 – Thousands of citizens surrounded Camp Aguinaldo and Camp Crame. Marcos made several attempts to disperse the crowd but did not succeed. Archbishop Sin went on Radyo Veritas to ask Marcos and Ver not to use force, while Aquino held a brief conference in Cebu and asked the people to support the military rebels and called on “decent elements of the military” to join the defectors.

Enrile and Ramos decided to transfer to Camp Crame and the people at EDSA created a protective wall around the troops as they left Camp Aguinaldo. Aquino also arrived in Manila and stayed in her sister’s house in Wack-Wack, Mandaluyong City.

By this time, General Artemio Tadiar had deployed tanks and Marine battalions to EDSA. The people formed human barricades and blocked the path of the tanks.

Marcos called Enrile and offered to grant him pardon but did not agree when Enrile demanded that the tanks be stopped. Enrile announced that he rejected the President’s offer.

Papal Nuncio Bruno Torpigliani gave Marcos a letter from Pope John Paul II asking for a peaceful resolution of the crisis. The United States White House issued a statement questioning “credibility and legitimacy” of the Marcos government.

Due to technical difficulties, Radyo Veritas signed off. Filipino broadcast journalist June Keithley, who had been broadcasting the rebellion since its beginning, took over DZRH radio in Santa Mesa, Manila to restart transmission.

February 24 – Church bells signaled that Marcos was planning an attack. People returned to the crowds that had been thinning when some of the tanks had left earlier. Tires were set on fire and sandbags and rocks were used to block the way to Camp Crame. That afternoon, Enrile warned that two Armored Personnel Carriers (APCs) were heading to Camp Crame. Human barricades led by nuns and priests prepared to block the path.

In the U.S., President Reagan agreed to give Marcos asylum. U.S. Secretary of State George Shultz asked Bosworth to tell Marcos “his time is up.” However, Marcos did not waver and vowed to wipe out the rebel troops.

Ver and Major General Josephus Ramas prepared for an all-out attack on EDSA with the use of tear gas, guns, and jets. Ramos calls on civilian reinforcements and, although fearful, rebel soldiers assembled for battle. Tear gas attacks started and helicopters began to approach Camp Aguinaldo and Camp Crame, but the civilians remained firm. By some miracle, soldiers had refused to fire and protesters had even given them flowers.

Rumors spread that Marcos had left the country, but these were soon silenced when he appeared on television and announced that he had no plan to resign or concede.

People continued to fill the area and Aquino stood before the crowd and spoke of the courage of the civilians in this fight with no bloodshed. She encouraged them to stay strong. “I enjoin the people to keep the spirit of peace as we remove the last vestiges of tyranny, to be firm and compassionate. Let us not, now that we have won, descend to the level of the evil forces we have defeated,” Aquino said.

Later that evening, the U.S. had issued a statement in support of Aquino’s provisional government. Marcos appeared again on television and said that he and his family in Malacañang were prepared for any eventuality.

February 25 – Two inaugurations transpired on this day.

Aquino was sworn in as President by Senior Associate Justice Claudio Teehankee, and Salvador Laurel as Vice President by Justice Vicente Abad Santos, at Club Filipino in San Juan. A crowd had formed around the venue to protect Aquino and her group in case Marcos loyalists attacked.

Meanwhile, Marcos held his own ceremony in the Malacañang’s Ceremonial Hall. The live broadcast was cut short as rebel soldiers captured the studios of the involved stations. The inauguration was reenacted and recorded by cameras.

A clash between pro-Aquino groups and Marcos loyalists took place at Nagtahan.

Marcos contacted Enrile to coordinate his and his family’s departure from Malacañang after U.S. Brig. General Ted Allen offered for them to use American helicopters to leave. The family packed their belongings, including boxes of money that have been stored since the start of his election campaign. Imee and Irene Marcos plead with there father to leave the Palace when he had informed some of his remaining men that he had decided to die there.

After negotiations with Aquino, the Marcoses and other government officials boarded helicopters and headed to the Clark Air Base where the family departed for Guam and finally to Hawaii.

Radio DZRH announced: “The Marcoses have fled the country.” U.S. Air Force TV Station FEN confirmed the report and the crowds rejoiced. Protesters began to storm the Palace. Looters and vandals took advantage of the situation, but Ramos’ men quickly moved in to secure the premises.

With that, the Filipino people regained their freedom from Marcos’ 20-year rule and marked a new era of democracy in the country.

Sources: gov.ph (https://www.gov.ph/edsa/the-ph-protest); “Chronology of a Revolution” by Angela Stuart Santiago; Inquirer Archives; https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/edsa/media/